What was the Tech-cession?

Understanding Why Tech Layoffs Started—and Stopped—and What it Means for the Rest of the Economy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 32,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

The start of this year was an especially terrible time for American tech companies. A combination of tighter monetary policy, rolling economic shocks, and a massive decline in technology usage after the early-pandemic surge left the industry in a fragile state. Collapses in financial titans like FTX and SVB put many companies in jeopardy, and worldwide venture capital funding began to dry up amidst rising interest rates. Firms like Facebook, now Meta, were taking big risks on new products only to seemingly burn billions with extremely little to show for it. Every week there was a new story about once-seemingly-unstoppable giants like Google and Amazon shedding employees, and the industry en masse became much more fearful in their tone and actions.

Yet the tech-sector layoffs that exemplified much of the downturn have themselves now mostly dissipated, falling significantly from their January peaks and actually shrinking on a year-on-year basis. Share prices for major tech companies have rebounded, with Meta up 150% since the start of the year, and executives are now excitedly talking up their AI investments rather than their headcount reductions.

In fact, the tech-cession layoffs have barely caused any contraction in overall industry employment, instead manifesting as a full stop in aggregate net job growth—a slowdown from the unprecedented hiring pace of 2021 and early 2022. America still has half a million more workers in tech industries than it did pre-pandemic, roughly as much growth as was seen from mid-2016 to the start of the pandemic.

Likewise, revenue growth in tech sectors has decelerated from its 2021 peaks but remains positive and high by many other industries’ standards—growth in the software publishing and computer systems design industries is even above 2019 levels. Combined with the employment data, it makes the tech-cession look more like a rapid expansion that got ahead of long-run economic fundamentals before slowing down dramatically, not a large structural contraction. However, even if the downturn did not involve much aggregate job loss it still has had important real spillover effects into the rest of the economy, including housing and wage growth—and it represents an important lesson about how economic narratives are formed.

So What Was the Tech-cession?

Much of what is considered the tech industry—software publishers, web search portals, social media sites, and computer infrastructure providers—falls under the “information” umbrella, making information sector-wide data a decent proxy for shifts in tech. In the second half of 2022, information layoffs hit their highest level since the start of the pandemic, clocking in at 300k before declining the following half. Quits likewise declined to the lowest levels since the start of the pandemic as the labor market loosened and fewer tech workers were transferring to new, higher-paying jobs. Yet it’s important context that the layoff rate as a share of total employment only barely crossed 2019 levels before turning back down, and the aggregate drop in information employment was only 1% and is partially explained by contractions in newspaper and magazine payrolls among other non-tech subsectors.

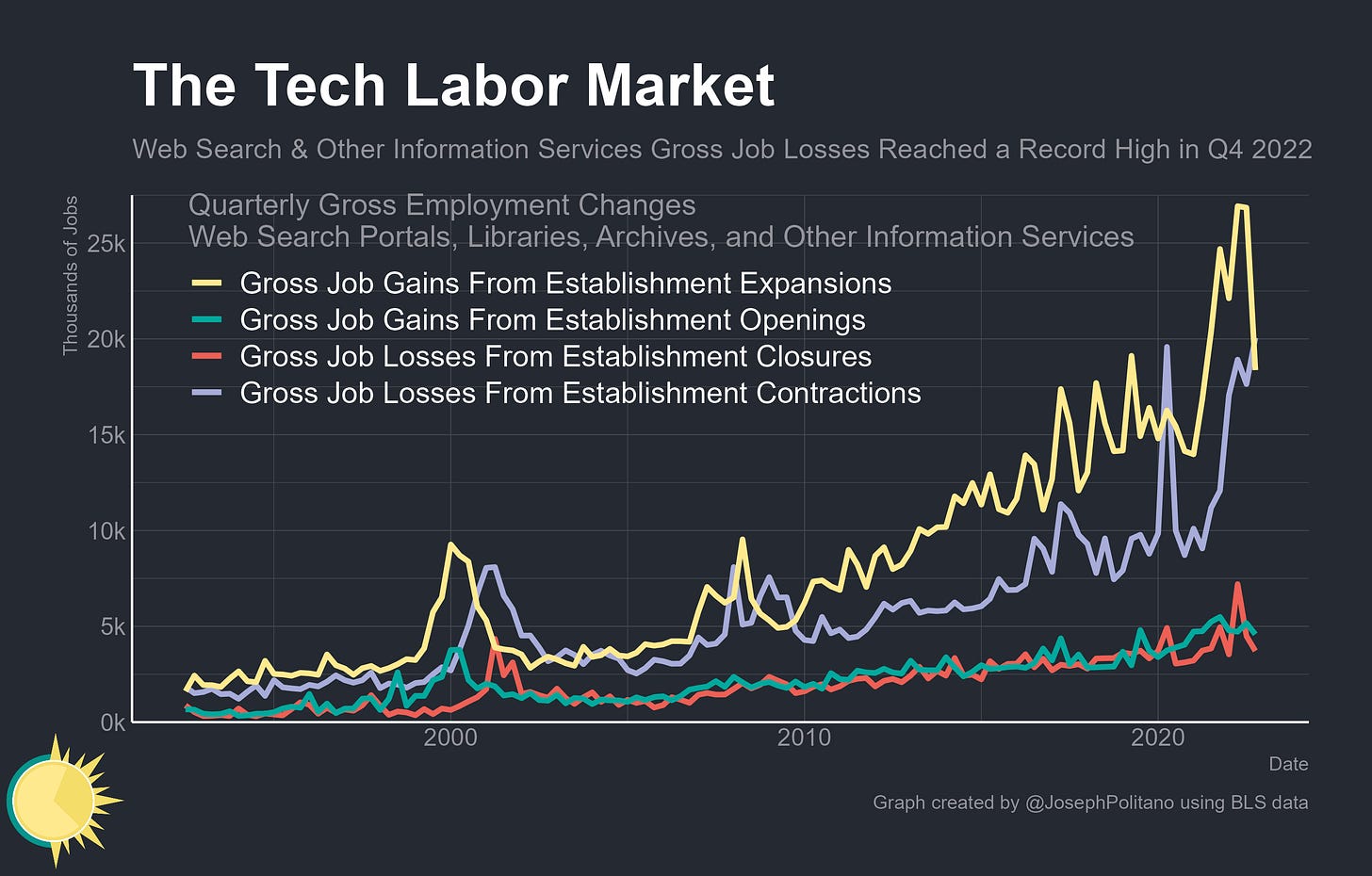

However, using recently released data from the BLS’ Business Employment Dynamics (BDM) program, we can now go beyond the headline numbers and look at the shift in tech employment in much greater detail than ever before. The BDM’s data is based on tax and unemployment forms businesses are required to file and can therefore track business establishments (individual offices of a company) quarter-to-quarter, which enables detailed breakdowns of tech employment by subsector and a granular look at which businesses are shedding or adding jobs and for what reasons. Looking just at the aggregate information sector, the surge following the start of the pandemic becomes especially clear—growing establishments were adding jobs at a pace not seen since the early 2000s and were dramatically outpacing the loss of jobs at contracting establishments. Likewise, openings of new establishments were adding more workers to the sector than at any point since the early 2000s and greatly outpacing closures. That reversed, quickly, in 2022—job gains at openings and expansions fell, while job losses at closures and contractions rose to the point that the sector was losing a small amount of jobs in Q4 2022. Keep in mind, however, that gross job losses are not all layoffs and gross job gains are not all hires—any net change in establishment-level employment, whether driven by hiring, quits, layoffs, transfers, or some combination thereof, gets counted.

Drilling into the computing infrastructure subsector, the story is much the same—gross job gains massively outpaced gross job losses for most of the pandemic before losses rose to meet gains at the end of 2022.

Web search portals is a slightly different story—this sector, despite its small aggregate labor force size, had been posting rapid continuous growth since the 2010s, driven almost entirely by establishment expansions. The pandemic resulted in a further massive bump in expansions but little commensurate bump in openings, while the 2022 slowdown resulted in record gross job losses from both closures and contractions.

Overall, the tech sector saw a dramatic slowdown in growth but extremely little employment contraction—the rise in gross job losses from closures and contractions rose to meet the declining level of gross job gains from openings and expansions in essentially all cases. Keep in mind, again, that the elevated levels of layoffs aren’t necessarily elevated layoff rates compared to pre-pandemic—rapid growth in tech industry employment means a constant firing of 1% of workers in aggregate shows up as significantly more raw job losses today. However, it would be a mistake to think that the downturn had no effect on the tech labor market or the broader economy—it’s just that the effect primarily manifested as massive drops in compensation rather than falling aggregate employment levels.

The Compensation Story

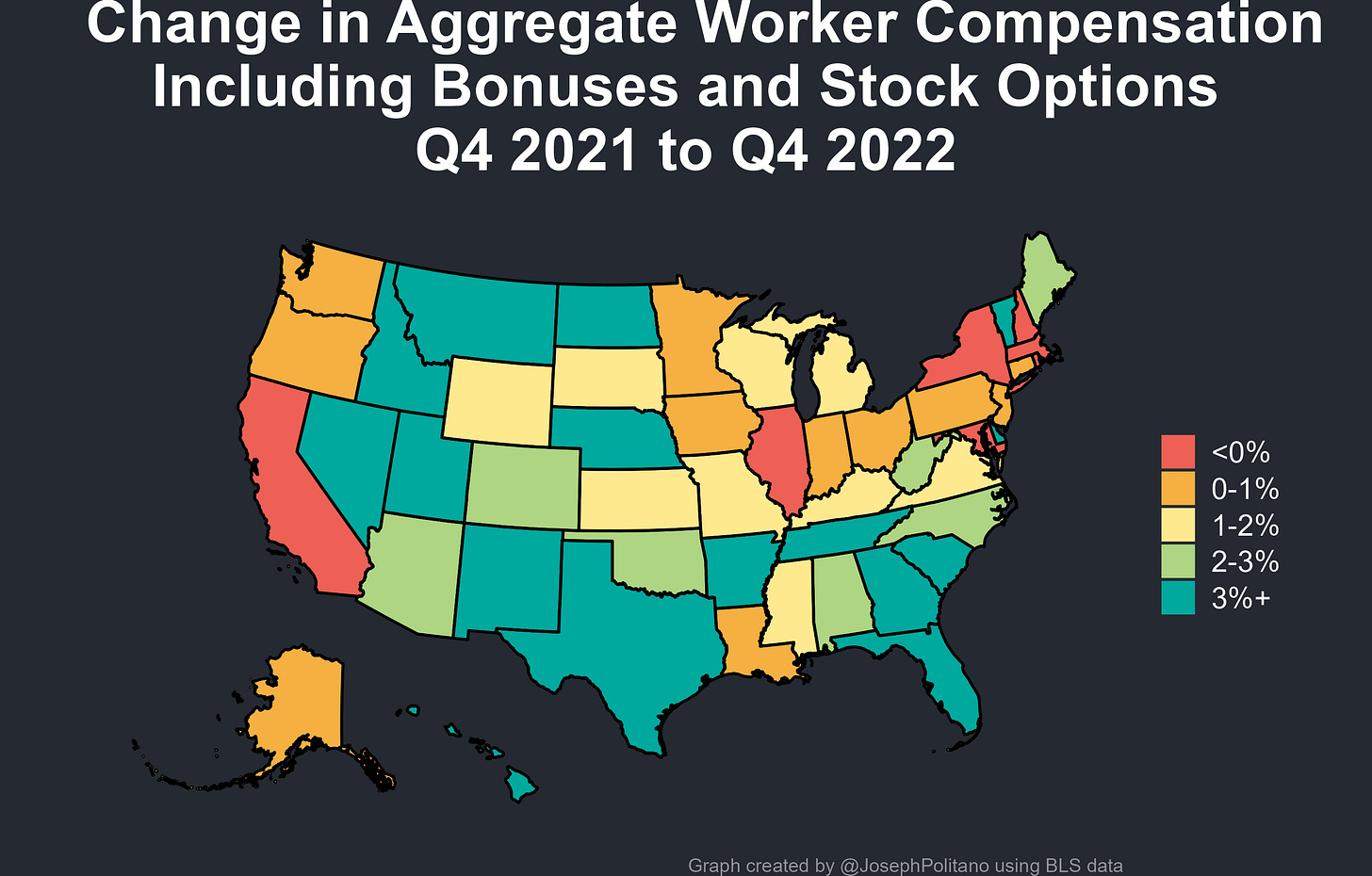

Tech workers are extremely well-paid—in 2021, the average annual compensation was $157k in custom computer programming services, $205k in software publishing, and $314k in internet publishing and web search—compared to a national average of only $68k. However, in many cases that pay is not evenly distributed, with the top percentiles of workers getting a large share of total money and significant chunks of compensation doled out as stock-based compensation or annual bonuses. That non-wage compensation boomed during the early pandemic before plummeting in the last year. With the caveat that this data is volatile, aggregate total compensation across tech industries grew at rates between 15 and 20% in 2021 before turning deeply negative at the end of 2022. With employment staying roughly the same and aggregate compensation tanking, per-employee pay was falling rapidly as well.

That fall in compensation from nonwage benefits was so strong that in many states it overpowered all wage growth elsewhere in the economy. California, alongside white-collar-heavy states like New York, Illinois, and Massachusetts among others, saw aggregate compensation fall over the year through Q4 2022 even amidst high inflation and historically strong nominal wage growth.

Indeed, aggregate private-sector compensation in California fell 4.3% in the year ending Q4 2022, the worst performance of any state in the union, and the downturn appears even starker when looking at the localities most directly attached to the technology sector. In the counties of San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara (home of San Jose), aggregate private-sector compensation fell between 15% and 20%, which helped to pull US growth down to practically 0%. That massive compensation fall is also likely responsible for some of the recent drop in bay area housing prices—over the last year, home values have fallen by 12% in San Francisco, 11% in San Mateo, and 8% in Santa Clara, some of the largest drops among major counties nationwide.

The effects were so large that California’s statewide economy could not help but be dragged down by the effects of the downturn. Real GDP growth in the Golden state outpaced the national average throughout almost all of the 2010s as the state’s superstar cities powered high-paying job growth and America’s growing tech economy, but 2022 saw California’s economy grow slower than the rest of the nation’s for the first time in years and even contract on a year-on-year basis in late 2022. Even though aggregate tech-wide job losses were minimal, the ripple effects of the dramatic fall in total wages were large.

The Tech-cession and Narratives of the Labor Market

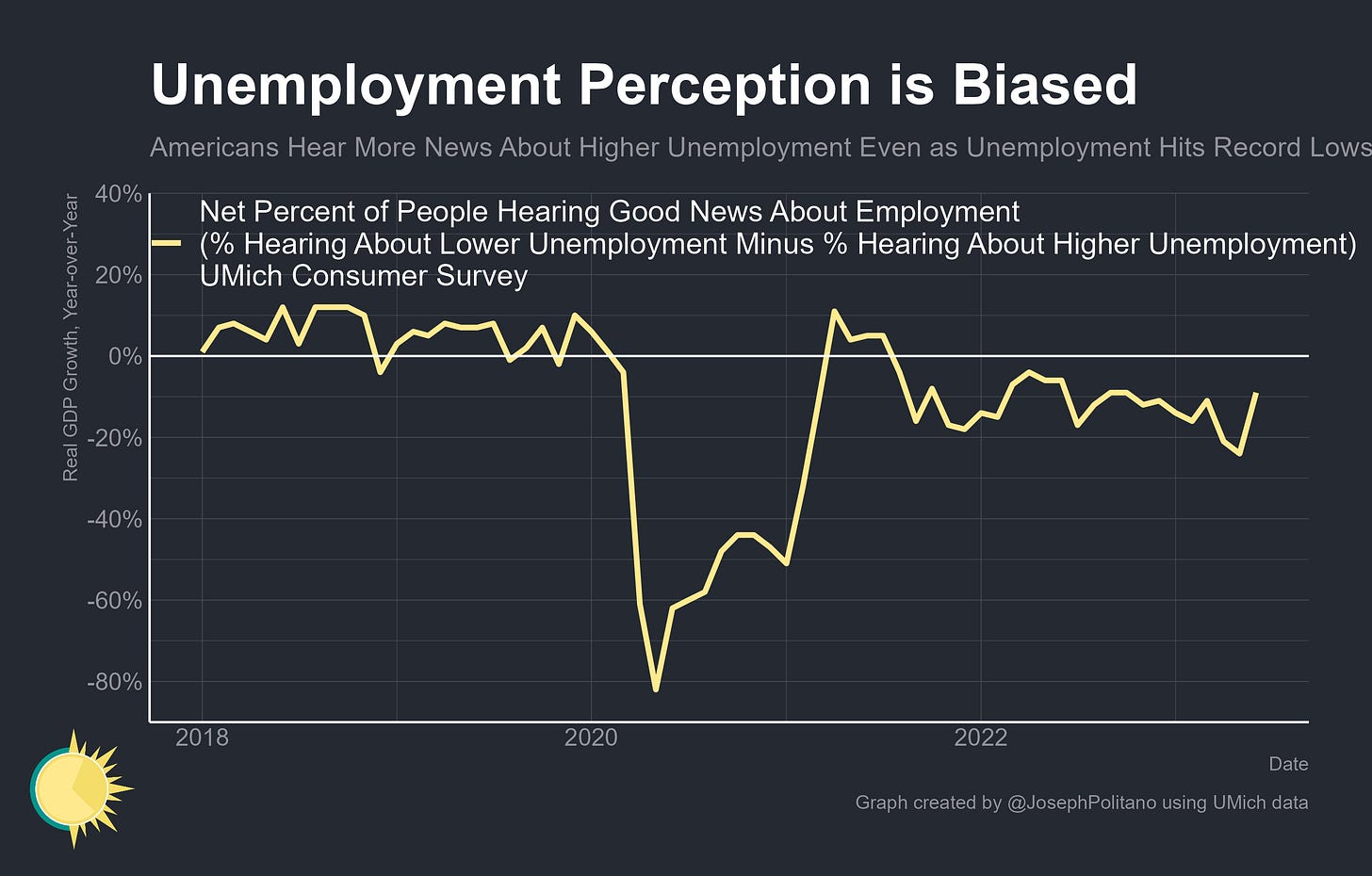

Still, it’s key to remember that although the tech sector and its employees have an extremely outsized presence in the overall economy by virtue of earning so much on a per-person basis, they represent an extremely small fraction of layoffs even amidst the tech-cession. Plus, although the labor market has cooled significantly from this time last year, aggregate US layoffs still remain well below pre-pandemic rates as employment levels continue to rise.

In fact, a large part of what made the tech-cession important was just the story itself—when major household names start laying off workers it is usually interpreted as a dismal indicator for the economy and becomes a widely-covered media phenomenon. Meanwhile, few of the healthcare, leisure, hospitality, or nonresidential construction firms that have dramatically increased headcount over the last year are household names, making their hiring decisions much less likely to make national news. The end result is that Americans are hearing more stories about rising unemployment than rising employment, even as US employment rates hit record highs and the economy adds jobs at a steady if slower clip. The natural bias of the media is to focus heavily on negative news stories that get more clicks, so regardless of the actual state of the labor market people almost always hear more about the subsectors that are contracting than the ones that are expanding. Given that media consumers are disproportionately upper-income white-collar workers, orders of magnitude more media attention are also paid to the slowdown in job growth in the tech sector than, for example, the simultaneous recent slowdown in employment growth for truck drivers and warehouse workers.

One thing remains certain though—for the last three years, cycles in tech have been detached from the rest of the US economy. The necessity of digital services during the early days of COVID-19 made it a uniquely strong sector during a historic nationwide recession and the economic shifts in 2022 made it a uniquely weak sector even amidst an economic slowdown. Historically, the popping of the dot-com bubble is remembered for crushing tech industry growth in its time, but it was arguably the protracted 2001 recession as much as sector-specific dynamics that led to the 2000’s long-term tech downturn. The concentrated tech-cession might be over, but the industry’s medium-term fate is still dependent on outcomes in the rest of the economy.

I'm pretty sure you've got CA and US as the wrong colors in this chart: https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdb8053b3-c861-4701-ade9-8e5a77d71889_2886x1843.png

Hey Joseph, great article. It's fascinating how the tech industry weathered through those tough times and bounced back. Looking forward to more insightful reads from Apricitas Economics.