Where is Russian Oil Going?

Mostly to India and China, Which is (Kind of) What the Sanctions Were Designed to Allow

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, the countries that backed Ukraine’s defense were stuck in a bind. They wanted to hit Russia’s economy as hard as possible in order to lower the country’s combat capabilities and deter further aggression, but they were acutely aware that the global economy relied on Russian exports of crude oil and refined products—and that European countries were extremely dependent on Russian natural gas for basic heating and electricity.

So they first struck from a different angle: Russia was subjected to some of the most stringent financial sanctions ever placed against a major country and was cut off from key complex manufacturing and consumer goods they imported from abroad. Yet energy commodities were mostly spared sanctions, with the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) explicitly laying out that sanctions do not prohibit all international transactions related to oil, natural gas, or coal. The message was clear: Ukraine’s allies wanted oil and gas to keep flowing and would instead look to limit Russian military and economic capabilities through export sanctions for key manufactured goods alongside broad financial sanctions.

These sanctions were extremely effective and the allies were able to inflict significant economic damage on Russia, though the contraction was smaller than initial expectations. Since then, Russia has retaliated by cutting off large swathes of Europe from natural gas and has begun replacing imports from allied nations with imports from other nations—especially China and Turkey.

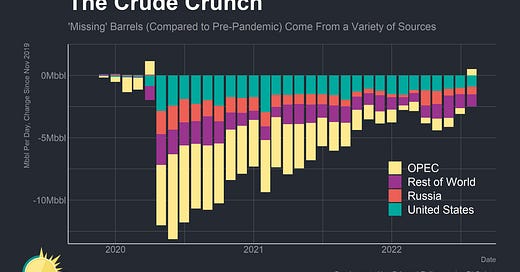

But after an initial drop, Russian oil output has remained comparatively strong—production was down “only” 700k barrels per day in September compared to the pre-pandemic high. Lighter energy sanctions have been reasonably effective in denying Russia export revenues from oil while keeping the black gold flowing—instead of selling to European and American companies at international market prices, Russia has been forced to sell oil to India, China, and other nations at significant discounts. Now, the EU looks to join the US in implementing a full ban on Russian oil imports and G7 countries are rolling out an international price cap of $60 a barrel for Russian crude. Their explicit goal is to continue maintaining Russian oil supplies while further denying the Russians energy export revenue:

This policy is intended to expressly establish a framework for Russian oil to be exported by sea under a capped price and achieve three objectives:

(i) maintain a reliable supply of seaborne Russian oil to the global market;

(ii) reduce upward pressure on energy prices; and

(iii) reduce the revenues the Russian Federation earns from oil after its own war of choice in Ukraine has inflated global energy prices.

These policies, however, do come with a tradeoff—capping Russian oil prices will likely lower Russian supplies, and the more stringent the cap the more likely supplies are to shrink. That’s why it’s arguably just as important that oil prices have declined significantly since this Summer, giving the G7 more leverage and flexibility in implementing sanctions. As allied countries work on tightening restrictions on Russian energy further, it will be critical to watch whether they can keep prices stable while limiting Russian revenues.

Russia’s European Oil Trade

EU imports of Russian crude oil, refined products, and refinery feedstocks have all declined significantly from both pre-pandemic and pre-invasion levels—with feedstock imports falling 65%, product imports falling 50%, and crude oil imports falling 25%. In aggregate the EU is still importing less than before the pandemic, but not much less than before the war—it’s just that they’ve swapped suppliers away from Russia while dealing with higher global oil prices.

However, the loss of Russian refined products and feedstocks did cause a refining capacity crunch that disproportionately boosted the prices of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel earlier this year. Prices for all three items have declined since then due to cheaper oil, but diesel and jet fuel spreads remain elevated compared to gasoline. That’s good news for American consumers, who mostly drive gasoline-powered cars and leave diesel for commercial trucks, but it’s bad news in Europe where diesel cars make up a large chunk of passenger fleets.

The other good news is that in Euro terms, EU imports of Russian oil and petroleum products have declined nearly 40% from their immediate post-war peaks. The decline in real imports obviously played a role, but just as important has been the decline in overall prices since the start of the summer. That still leaves Europe sending Russia significant amounts of money for oil imports in addition to paying the rising costs of natural gas. On net, that’s kept EU imports from Russia at approximately pre-pandemic levels in Euro terms, though lower in real terms.

So that begs the question—if Russia isn’t sending as much energy to Europe, where is the energy going? Part of the answer is that there’s just less of it—Russian natural gas output is down more than 20% as Russia finds it much harder to find willing and able buyers due to infrastructure constraints and sanctions. Oil, however, is more flexible and fungible—it does not require the pipelines or hyperspecialized transportation equipment that natural gas does and can be moved around much easier. Russian oil production is only down a couple of percentage points from pre-pandemic levels—so if it’s not going to Europe, it must be going somewhere. The answer is that Russia is selling more oil and other energy products at significant discounts to less scrupulous nations with fewer ideological and geopolitical commitments to Ukraine—increasingly, that means China and India.

Where is Russian Energy Going?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.