Why You Should (and Shouldn't) Fear a Yield Curve Inversion

It Can't Quite Predict Recessions, but it Might Help You Understand the Stance of Monetary Policy

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

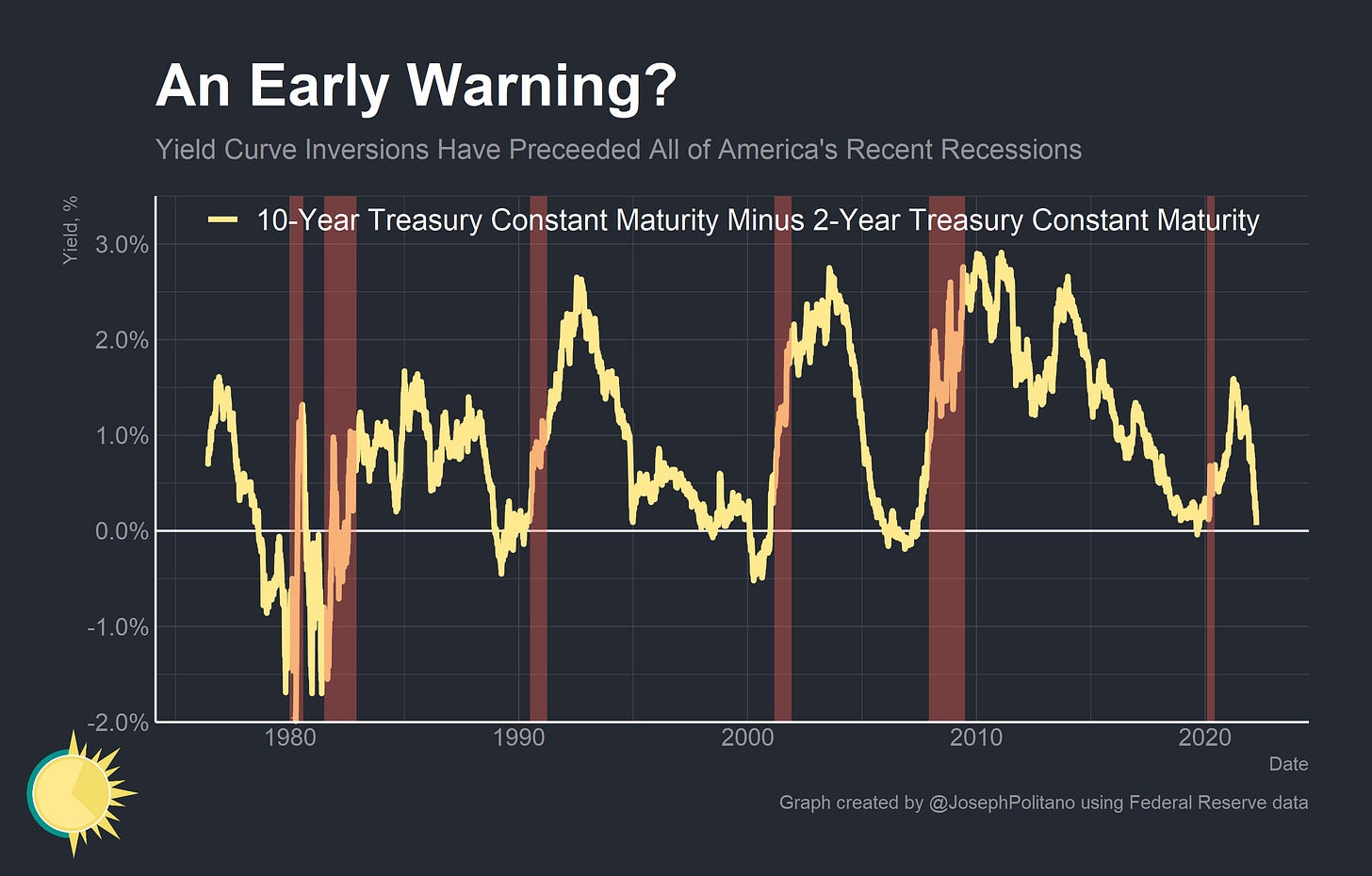

Yesterday, a supposedly important recession indicator flashed red. For a brief moment, the market yield on a 2-year Treasury bond exceeded the yield on a 10-year Treasury bond, making the yield curve partially inverted. By the end of the day the 2s10s spread had gone positive again, but closed at a meagre 6 basis points—leaving the yield curve extremely flat. People remain worried for one simple reason: every American recession in the modern era has been preceded by a yield curve inversion.

Indeed, the 2s10s spread has been sinking like a rock since the start of this year as the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy to combat inflation. This begs the obvious question: is the Fed tightening so aggressively that it will cause a recession while trying to tame inflation?

Well, the yield curve’s apparent consistency as a recession indicator is less ironclad than it initially appears. For one, the brief yield curve inversion of late 2019 did not cause or predict the pandemic-induced recession of early 2020. For two, yield curve inversions actually occur 19 months before recessions on average, and sometimes the curve un-inverts before a recession actually begins. Also, the yield curve’s predictive record is much messier outside the US. If a recession is imminent the stock market sure didn’t notice: the S&P 500 closed the day up nearly 1.25%. And different parts of the yield curve are saying different things right now. That’s because yield curve inversion isn’t a simple predictor of a recession—though it might give you some important information on the stance of monetary policy.

Upside Down and Backwards

To understand a yield curve inversion, it is first necessary to understand what determines the yield (the interest rate) on government bonds. I have written about this in greater length before, but in general the best way to think about bond prices is in terms of expected future short term interest rates, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, and credit risk. Credit risk—the risk that a debtor defaults—is functionally zero for the US government since the Federal Reserve can always backstop federal debt. Liquidity risk—the risk that an asset will not be easily convertible to cash—is (outside of crisis periods) consistent across time and low for Treasuries, so it can be ignored for now. That leaves expected short-term interest rates and interest rate risk.

Expected short term interest rates are fairly simple: if an investor expects the effective interest rate on cash1 to be 2% over the next two years, she will not be interested in purchasing a two year Treasury at a 1% interest rate. A rise in market expectations for effective overnight interest rates over the next two years will therefore manifest as a similar rise in two year Treasury yields. They will not rise in tandem, however—partially because the two year Treasury note carries additional interest rate risk. If the expected yield on cash rises, investors who bought two year bonds will be stuck with their lower initial yield. To be compensated for this interest rate risk, bond investors demand a yield premium over the expected cash rate2. In general, this means that yield curves will be upward sloping: longer-maturity bonds carry more interest rate risk and therefore command a higher yield premium than shorter-maturity bonds.

Indeed, that is what yield curves looked like between December and early March. The Federal Reserve started signaling higher expected short term rates as they tightened policy to combat inflation, leading the yield curve to rise. The curve was also flattening pretty rapidly: the yields on short-term government bonds were rising faster than the yields on long-term government bonds. Still, the curve was uninverted until relatively recently.

Today the yield curve is steep and uninverted from 1 month to 3 years, then inverts dramatically from 3 years to 10 years. What could explain this? Well, let’s return to our previous model and, for a moment, presume that relative interest risk is unchanged. The only thing that could explain the shape of the yield curve is that investors expect short-term interest rates to rise dramatically over the next 3 years and then slide downwards for the following 7 years. Critically, investors would have to expect rates to slide down significantly: the decline in rates would have to be large enough to overpower the increased interest rate risk on longer maturity bonds.

When you put it that way, a yield curve inversion doesn’t seem so scary—just an expected drop in short term interest rates sometime in the future. But that’s underestimating the risk at hand—investors usually expect short term interest rates to decline in the future because they are pricing in a higher risk of a recession. That may be part of what is going on right now: short term interest rates are rising rapidly, financial conditions are generally tightening, and longer-run growth prospects are weakening. The risk is that the Federal Reserve raises interest rates so fast in 2022-2022 that it hampers economic growth—forcing nominal interest rates to go lower from 2025 to 2032. But in truth the inverted yield curve only tells you that investors expect short-term nominal interest rates to rise and then fall—not necessarily that they expect a recession.

Imminent Danger?

Indeed, while the 2s10s spread is the most newsworthy part of the yield curve, Economists Arturo Estrella and Mary Trubin at the New York Fed posited that the 3 month/10 year spread is actually the best statistical indicator of a recession. That spread has actually increased since the start of the year, though the Fed’s hiking cycle may quickly raise the yield on three-month Treasury bills, dragging it back down. Economists Eric Engstrom and Steven Sharpe prefer what they call the “near term forward spread”—defined as the difference between the yield on 3 month Treasury bills now and 6 quarters in the future. That metric has also risen significantly in recent months, which they interpret as a strong counterargument to fears about the 2s10s spread inverting.

Another data point against elevated recession risk is the drop in recent drop in corporate bond yield spreads. These spreads measure the relative difference in yields for corporate bonds relative to treasury bonds, and so are a good proxy for how difficult it is for major corporations to borrow. They also provide critical information on the market’s assessment of default risk for major companies. If the probability of a recession was rising, one would expect that investors would be more worried about firms defaulting on their debt. Yet in the last two weeks corporate bond spreads have decreased by 20 basis points. Spreads on high yield corporate debt are also down 50 basis points, although this could be partially due to the overrepresentation of energy companies among high-yield bond issuers and the recent rise in energy prices. But if elevated recession risk isn’t driving the inverted yield curve, what is?

For one, increasing volatility around interest rates (especially interest rates over the next two years) could be driving the yield curve inversion. Earlier I said that for the sake of argument we should assume that relative interest rate risk remains unchanged—but in practice this is an unrealistic assumption. Interest rate risk is constantly changing, and can change more or less for bonds of different maturities. Between the Federal Reserve’s tightening cycle, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the changing severity of the pandemic, there has been a lot of additional interest rate volatility in markets. The MOVE index, which measures bond market volatility, has been increasing significantly since late 2021. Given the constant back and forth about the specifics of the Federal Reserve’s plans over the next couple years (all the talk of possible 50 basis point hikes, for example), it is possible that the interest rate risk on shorter-maturity Treasuries has risen faster than the risk for longer-maturity Treasuries. Given the increased convexity of longer-maturity bonds (the relationship between interest rates and interest rate risk) higher volatility in expected short-term rates could actually be pulling long rates relatively downward. That could drive a yield curve inversion even if market participants do not expect a higher probability of a recession.

The other thing that could drive the inverted yield curve is, well, inflation. Market-based measures of inflation expectations are currently pricing in fairly high inflation over the next 5 years, and then lower inflation from then on. If you dig deeper into Consumer Price Index (CPI) swaps, it becomes clear that inflation expectations are high for the next 1 year, slightly above normal for 2023, and then come back down to normal. It is theoretically possible for nominal interest rates to rise over the next couple years and then fall while real interest rates remain relatively constant. If market participants expect that, it would mean the yield curve would be inverted even though recession risk would be minimal.

Finally, investors might expect Jerome Powell to simply back off the hiking cycle at some point. If you think about the 2019 yield curve inversion, investors essentially expected the Federal Reserve to lower rates in order to stave off the slowdown and eventually the Federal Reserve did so—all without a recession.

Conclusions

I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.

James Carville

In a recent working paper, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French found that using inverted yield curves to predict recessions proved bad financial advice: 67 of 72 global term spread strategies underperformed passive equity investing. That’s partially because the yield curve has a worse predictive track record outside the US, failing to predict any Italian recessions while littering Canada and the UK with false positives. That’s also partially because the yield curve gives off shifting signals: the 2s10s spread went negative in early 2006 before bouncing back by mid 2007, way before the 2008 financial crisis reached its worse. There’s also always some degree of backtesting bias in terms strategies: with so many different spreads to choose from and a relatively small sample of recessions, there will always be one spread that looks like a good recession predictor by pure happenstance.

To some extent, this shouldn’t be surprising: if there was a guaranteed recession indicator then it would be relatively easy to simply identify and prevent recessions. Instead we live in a complicated world with a million confounding variables. Still, the yield curve isn’t useless: knowing that investors likely expect nominal interest rates to decrease sometime in the future is important to assessing the economic outlook. This is especially true because there are so few market-based measures of monetary policy expectations. There is no massive futures market for gross domestic product or employment, so the bond market often represents the least-bad way to assess market participants’ outlook. However, it is always necessary to put bond market movements in context with other economic data points.

“Cash” is a bit of a difficult thing to get a single interest rate on in practice, as regulations and other irregularities can lead to different institutions having slightly different interest rates available to them.

A lot of models will have list different risk premiums for government bonds, but in truth these are just a decomposition of interest rate risk. Take inflation risk: if inflation rises, nominal interest rates will also rise (for a given real interest rate), so inflation risk is really only part of what constitutes interest rate risk.

Increadible read, better and in much greater detail than any textbook or trader ever explained it to me!

Thanks especially for mentioning the yield curve as a predictor in countries outside the US. I've been looking at the UK 2s10s for a while, but that seems to be a bit of a futile exercise.

Hey Joey - thanks for the post.

Do you have any more resources on the short-term rate vol impact on long term bond yields outside of Emanuel’s tweet? Wondering if this is part of the effect, why it may be impacting 2yr more than longer maturities. I have some ideas, but any more reading you’ve come across on this would be super interesting.