The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

As the US economy has come roaring back from the pandemic, inflation concerns have come roaring back as well. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has grown by 0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.5% respectively over the last three months. Year-on-year inflation has exceeded 5% each of the last three months as well, driven in part by base effects from pandemic-driven low prices in the Summer of 2020. However, there is still not enough evidence to justify excessive concern of persistent above-trend inflation. Today’s inflation is driven more by abnormal, idiosyncratic price increases driven by the pandemic than by monetary policy, and will abate as economic reopening allows demand and supply to renormalize.

Despite the extreme changes in the economy over the last two years, market-based and consumer inflation expectations have not significantly increased above the pre-pandemic level. The unemployment rate, at a high but not apocalyptic 5.4%, belies the significant improvements necessary before America achieves full employment. Economic stimulus is waning as the federal government winds down much of its pandemic relief initiatives. In the coming year, the reduction in government support for aggregate demand is more likely to pull inflation downward than to increase it. As the end of supply shortages couples with minor shortfalls in aggregate demand inflation will decrease back to normal levels.

The Federal Reserve’s new framework calls for above-trend inflation for a short period of time to balance for periods of below-trend inflation and improve labor market conditions. However, the Federal Reserve has struggled to clearly communicate the precise targets and goals of Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT), resulting in increased uncertainty about the future path of interest rates. Calls to tighten monetary policy have cropped up now that PCE inflation has exceeded 2% for several months and the PCE price index has generally caught up with its pre-COVID trend. These calls are based on a core confusion - the transitory inflation we are currently experiencing is more a result of pandemic-related shortages and price swings rather than improved economic conditions. The Fed should not tighten policy in response to these extreme short term price fluctuations and should instead maintain its expansionary policy stance until sustained above-trend inflation is coupled with a strong economy, high levels of employment, and significant wage growth.

Pandemic Prices

First of all, it is important to note that the Federal Reserve uses the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI) instead of the CPI as its monetary policy target. This is for good reason - the CPI explicitly only tracks the spending patterns of consumers’ discretionary income instead of total spending in the economy and is not methodologically comparable to the PCEPI. Over long periods of time, the CPI tends to overstate inflation due to these weighting and methodological differences, which is why it is almost never proper to use CPI to deflate values over long periods of time. Focusing on PCEPI instead of CPI, what does inflation look like?

2020 saw the greatest level of year on year PCE inflation in American history, driven in part by base effects from the drop in prices early in the pandemic. Essentially, the pandemic drove prices down in the immediate aftermath of March 2020 making calculations of inflation for Summer 2021 overstate the rise in price level since before the pandemic. PCE has gone above the pre-pandemic trend, meaning that inflation is above the Federal Reserve’s 2% long-run target, but it is not the catastrophic story that the year on year figures indicate.

Looking at core PCE inflation, which is the PCEPI minus items with traditionally volatile prices like energy and food, we see only a slightly lower rate of inflation. Usual core inflation metrics are failing in the face of the pandemic as COVID drives idiosyncratic price increases among traditionally stable goods and services. Trimmed mean PCEPI, which is the PCEPI excluding the items with the most extreme price changes, has actually remained relatively stable since the pandemic began and has not even cleared the Federal Reserve’s 2% target.

Essentially, dramatic price increases in a select few items are driving inflation higher, not broad-based increases in the price level. Trimmed mean PCEPI presents the best view of structural inflation, the kind caused by excessively loose monetary policy. It explicitly ignores the narrow price fluctuations that cause excessive noise in the headline and even core PCE inflation rates. Trimmed mean inflation remained stable when a massive drop in oil prices tanked PCEPI in 2015 and critically showed lower price increases in 2008 than the headline inflation numbers that scared the Federal Reserve into keeping interest rates too high. Using trimmed mean inflation to guide our understanding of inflation and monetary policy, it becomes clear that the Federal Reserve’s policies are not too loose and are not the primary drivers of current inflation. Extreme price fluctuations outside the Federal Reserve’s control are driving inflation at the moment.

Take, for example, used cars and trucks. For nearly ten years, the nominal prices of used vehicles tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics remained practically unchanged. In the last two years alone prices have skyrocketed more than 40% as COVID-wary travelers exit public transportation en masse and a dire shortage of semiconductors impairs car manufacturing. These price increases have little to do with the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy and much to do with the specific circumstances of the pandemic.

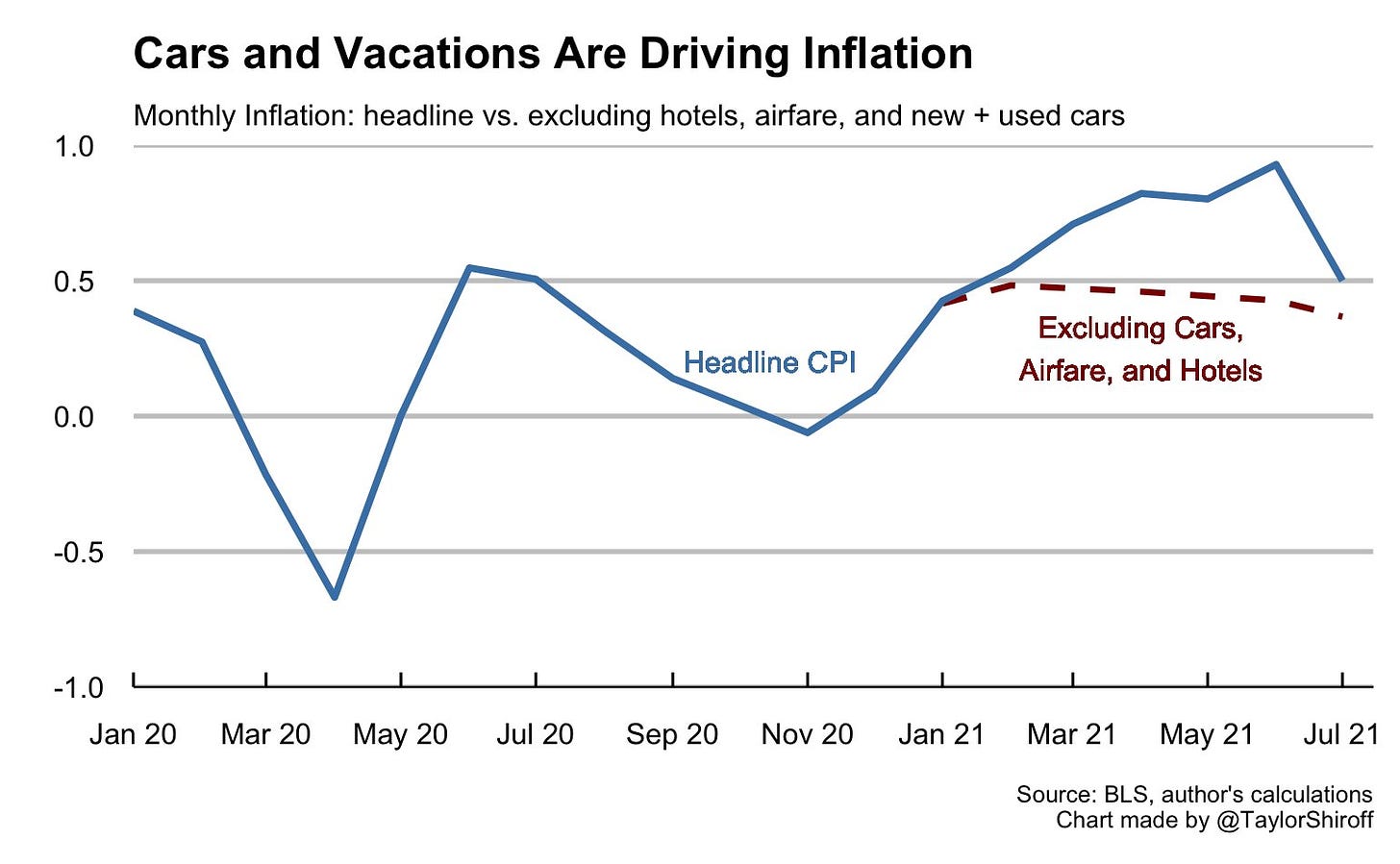

These narrow price spikes have had measurable impacts on the headline inflation measures. Excluding cars, airfare, and hotels would lower monthly inflation significantly for all of 2021 - by as much as 50% in some months! Though there are still severe supply issues now, It is likely that as the pandemic abates demand will renormalize and supply chain issues will ameliorate such that we will see a significant price decreases in affected sectors. Even though prices may not completely return to their pre-pandemic levels, they will pull future inflation down significantly as they decrease.

Finally, it is worth noting that the Federal Reserve has explicitly sought to increase short term inflation under its new FAIT regime. In the past, the Federal Reserve has targeting 2% inflation, but this target has instead felt more like a ceiling. Whenever inflation threatened to clear the 2% target, the Federal Reserve would preemptively raise interest rates and tighten monetary policy. The result is that long-run inflation has persistently remained below the 2% target and economic growth has been hampered by overly tight monetary policy. Under FAIT, inflation will be allowed to persist above the 2% target for a certain period in order to boost unemployment and keep long run inflation expectations anchored to 2%.

As the chart above shows, average inflation since the framework revision has recently inched across the 2% target. This has resulted in mounting pressure for the Fed to tighten monetary policy again, but critically does not represent the kind of transitory inflation called for by FAIT. There are two types of transitory inflation that often get blended together into one idea. The first is the transitory pandemic inflation we are currently experiencing: massive shifts in supply and demand caused specifically by COVID that are causing price increases in certain sectors. The second is the transitory inflation driven by the Federal Reserve finding “full employment”: broad increases in the price level throughout the economy as a result of aggregate demand reaching its sustainable maximum. To the extent that those within the Federal Reserve confuse one for the other, they risk keeping monetary policy too tight in order to stave off inflation that was not actually caused by monetary policy. This was part of what occurred during the 2008 crisis - the Federal Reserve was too focused on short term inflation numbers to lower interest rates quick enough to counteract the crisis. To fulfill the promise of FAIT, monetary policy must be kept as expansionary as possible until employment and economic growth find their sustainable maximums.

The Employment Situation

How close are we to the sustainable maximum levels of economic growth and employment? Not particularly close.

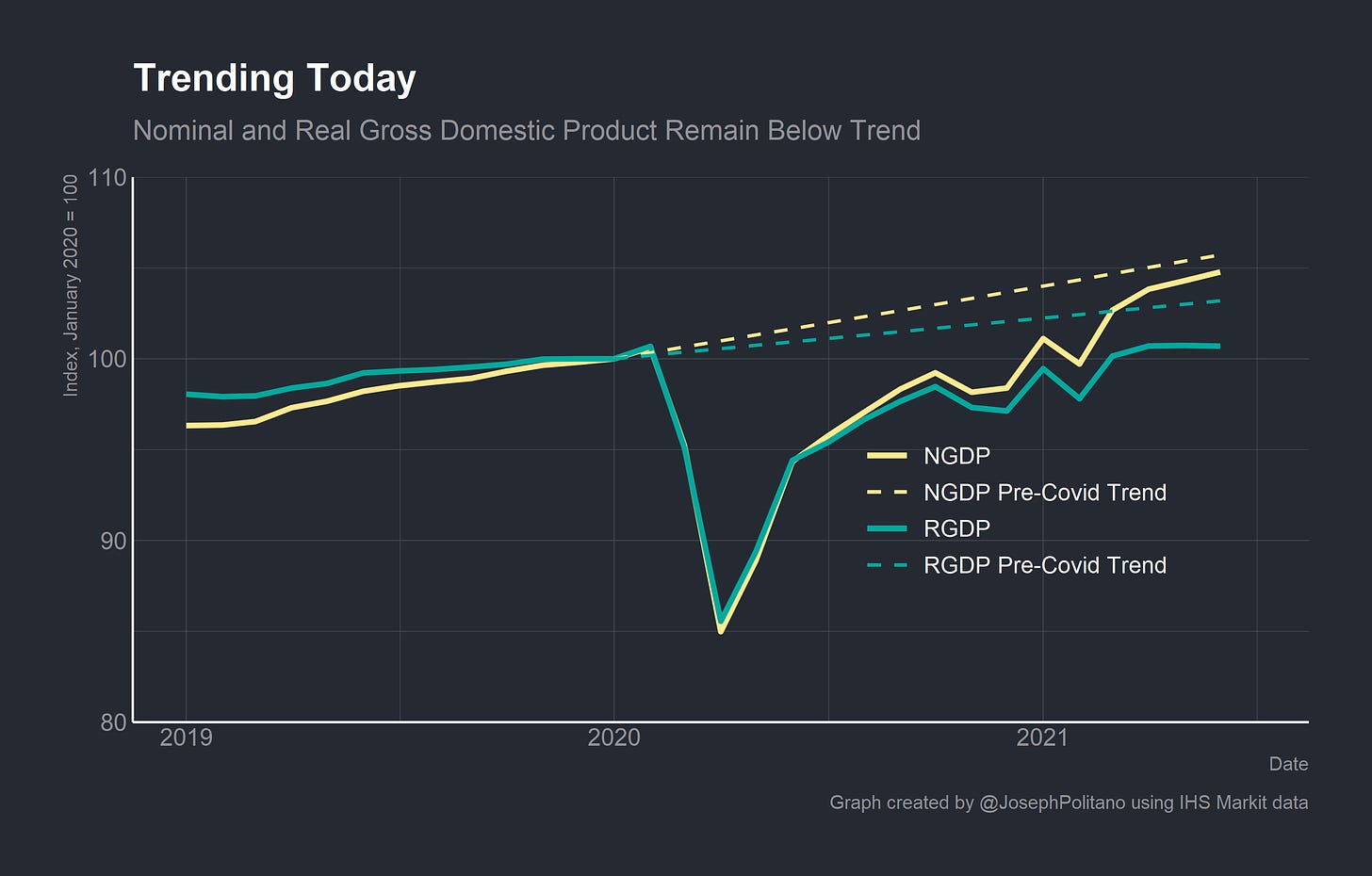

Nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) remains marginally below the pre-COVID trend, and real gross domestic product (RGDP) has barely scratched the pre-COVID level. Given that NGDP, like inflation, should exceed the trend growth rate to make up for periods where it goes below trend, policy should not suddenly become contractionary when the NGDP gap is closed.

Employment also remains unacceptably low. Even though the economy has rebounded fairly quickly since March 2020, millions of people are still unemployed or have left the workforce entirely. Even when the prime-age employment-population ratio, a measurement of the amount of working age people who have a job, reaches the pre-pandemic level it will be nowhere near the historical maximum. Given the increased participation in America’s peer nations, there is also no reason to expect that 1990s employment-population ratio represents today’s full employment. In short, there is a long way to go before the labor market as strong as possible.

Given how tightly intertwined nominal GDP and labor market strength is with aggregate demand, I see no reason to worry that the short-term burst of inflation we are currently experiencing will persist as the pandemic fades. The reality is that weak employment and sagging GDP growth is more likely to occur when stimulus policies from the federal government and Federal Reserve fade away, especially if monetary policy is tightening in response to pandemic-driven transitory inflation. In order to find full employment and maximum economic growth, the Federal Reserve must distinguish between the framework-driven and pandemic-driven versions of transitory inflation and should confidently keep policy as expansionary as possible until it achieves its framework’s objectives.

While inflation has been eating into real wages as shown on the graph above, it is worth noting that framework-driven transitory inflation is the best outcome in regards to long run wage growth. During recessions, especially demand-driven recessions, downward nominal wage rigidity means that some employees tend to get laid off rather than all employees experiencing a cut in their wages. Downward nominal wage rigidity means that for psychological, contractual, legal, and other reasons it is extremely difficult for employers to reduce the nominal wages of their employees for any reason. Imagine if your employer attempted to cut your hourly wage today - how would you react? Add to that the fact that many employees have contractually obligated salaries or that many workplaces have structured wage bands so that similar employees have the same wage and suddenly it becomes easier for employers to fire a certain proportion of employees rather than trying to lower wages across the board.

In a situation where deflation occurs during a recession, real wages can spike significantly even as nominal wages remain the same. That is what happened at the onset of the 2020 and especially 2008 recessions, and it was partially responsible for the large spike in unemployment that occurred both times. Now, the importance of downward nominal rigidities is often overstated - aggregate nominal wages are not that sticky when you account for job-changers and nominal wage rigidities only catalyze, but do not cause recessions. Additionally, nominal balance sheet (people pay bills and debts with nominal wages, not real wages) and nominal expectations (people plan with expectations of nominal income more than real income) factors likely matter just as much if not more than nominal wage rigidity. Changes in gross nominal income growth, particularly gross labor income growth, are the primary demand-side mechanisms by which recessions occur.

My only point in bringing this up is to say that that the real threat is hysteresis - persistently low aggregate demand and economic growth caused by unemployment, itself caused by persistently low aggregate demand and economic growth. If we boost nominal incomes sufficiently we can prevent the nominal income, balance sheet, and expectations issues that plagued the post-2008 recovery. The result in 2008 was nearly five years of no real wage growth and high unemployment. If transitory inflation breaks us out of nominal constraints, the short drop in real wages we are currently experiencing will be followed quickly by increases in real wages and employment.

Conclusions

None of this should be construed to argue that excess inflation is a good thing, or even a necessary part of strong long-term economic growth. It is only an acknowledgement of the current state of affairs surrounding inflation and the necessary steps to get to full employment. If the Federal Reserve is targeting inflation expectations and working to keep them anchored at the 2% target, it must be both forward looking enough to prioritize future inflation over past inflation and strong enough to tolerate short-term deviations from the target in both directions.

Critically, the Federal Reserve must also distinguish between current pandemic-driven transitory inflation and future framework-driven transitory inflation. Instead of tapering asset purchases and considering raising interest rates in response to current inflation, the Federal Reserve must acknowledge that expansionary policies remain necessary to prevent nominal income from shrinking. M2 money supply growth has dramatically decreased, despite M2 money velocity remaining at historical lows. Market-based inflation expectations remained anchored at levels near 2%, and model-derived levels of inflation expectations are still below 2% even for CPI. The federal deficit is decreasing as enhanced unemployment benefits expire and pandemic relief is pulled back. Adding tightened monetary policy to the mix will pull down aggregate demand from its fragile state and risk elongating the crisis.

In 2007, 2015, and 2018 the Federal Reserve preemptively tightened policy out of misplaced fear of oncoming inflation, only to reverse course later and loosen monetary policy in order to support the economy. If the Federal Reserve does not learn from these prior experiences and stick to their new commitment to create policy-driven transitory inflation they will deal irreparable damage to both their credibility and to the economy. Today’s inflation is transitory, and policymakers should not react to it by pre-emptively tightening monetary policy.