You Asked, We Answered! On Monetary Policy, Housing, and Hot Takes

Kyla and I Answer the Questions You Submitted!

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

This post is partnered with Kyla Scanlon, who writes her own newsletter (which you should subscribe to). Over the last several weeks, we’ve been collecting questions from readers. Today, we’re finally answering the best ones—with a twist! Half of our answers are posted here, and the other half are posted in her newsletter at the link below:

Be sure to check out her post where we answer whether crypto wealth is too concentrated, if today is a repeat of the 1970s, and how to square rising NFT and commodity prices. Now, onto the show!

Is the Fed’s independence at stake?

Joey:

Yes, but not from the current bout of inflation. Independent central banks have endured worse and longer-lasting policy errors in recent memory (the post-2008 Federal Reserve, the ECB during the Euro Crisis, Bank of Japan for most of the last 30 years) without losing their independence. In fact, a loss of independence usually comes before a bout of inflation (like what’s happened to Turkey recently) not the other way around. But in general, nothing in the social media age can remain both salient and unpolarized. The Supreme Court an illustrative example here: as hyperpartisanship made passing laws more difficult, focus instead shifted towards using the Supreme Court to achieve political goals. The result is partisan bickering that makes appointing new justices a toxic process and has reduced public trust in the Supreme Court.

We’re already seeing that happen to central banks around the world—because they are generally successful institutions, elected leaders are looking to use them to achieve political goals. The New Zealand government added a mandate to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand requiring it to control home prices, and the British Parliament added language on “environmental sustainability and the transition to net zero” to the Bank of England’s mandate. Regardless of your opinions on the policies, it represents an uncomfortable expansion of monetary policy’s role in the economy. Add to that the polarization of central bank appointees (Trump’s refusal to renominate Janet Yellen as Chair and the recent collapse of Sarah Bloom Raskin’s nomination are two examples) and there is serious long-term risk to the functioning and independence of monetary policy authorities.

Kyla:

What is the Fed’s structure? So the Fed is sort of pseudoindependent (scientifically known as “independent within the government) - they got their power in 1913 from the Federal Reserve Act, where Congress delegated the Fed the power to regulate money. The Fed is not funded by Congress (the Fed is self-funded through interest earned on securities and depository institution service fees ec etc, so they are not reliant on the government for money), they don’t really need to check with the President, and they serve 14 year terms in order to have them make long term decisions (which brings up a whole question around our 2-4 years for politicians).

However: They do get oversight from Congress - which can influence how the Fed is structured. It’s the main reason why Sarah Bloom Raskin ended up withdrawing (turns out you shouldn’t care that much about climate change)

So *is* the Fed independent? In short, yes. The reason that the Fed is independent is because the Fed has their dual mandate - (1) price stability and (2) maximum employment, and everyone wants to make sure that politicians don’t slide in to try and make stuff go their way.

But a lot of people don’t like this independence: There’s a lot of questions that come up with the Fed - mostly the “wow why is this this-group-that-is-unelected-by-the-American-public making decisions for everyone??” That’s *why* the Fed testifies before Congress twice a year - so Congress can grill them - but largely, monetary policy needs to be independent so it isn’t impacted by short-termism.

The question is always - are they doing the best thing for the American people? That’s why they exist, right? Many think so but also I think that everything that gets clouded by incentives (politics are going to politic). So it’s being more political - using intermeeting minutes to sort of announce policy decisions, the politics of inflation, politician finger pointing - monetary policy has become an election cycle.

Will the housing bubble burst?

Joey:

Let’s take a step back first: is there a housing bubble? A “bubble” is distinct from simply “high and rising prices”, and almost by definition a bubble will eventually burst, so “is there a housing bubble?” is the more interesting question. For nearly a decade people have been calling the top of the housing market, but home prices march on ever higher. That’s because interest rates have been low, household income is growing, and building rates are extremely low. That last piece is extremely critical: today, new housing starts are 12% below their 2006 peak and have been well below today’s rate throughout the 2010s.

That’s alongside a longer backdrop of shrinking household sizes (as people marry later in life) and rising populations (as life expectancies grow). Households in general are demanding more space, and a lot of America’s old housing stock simply isn’t providing it. The fundamental cause of America’s home price boom has been an unprecedented shortage of housing units: that’s why vacancy rates are declining and real rents are rising. Rising mortgage rates and slower household income growth will cool home price growth, but prices will remain too high as long as there are too few housing units.

Kyla:

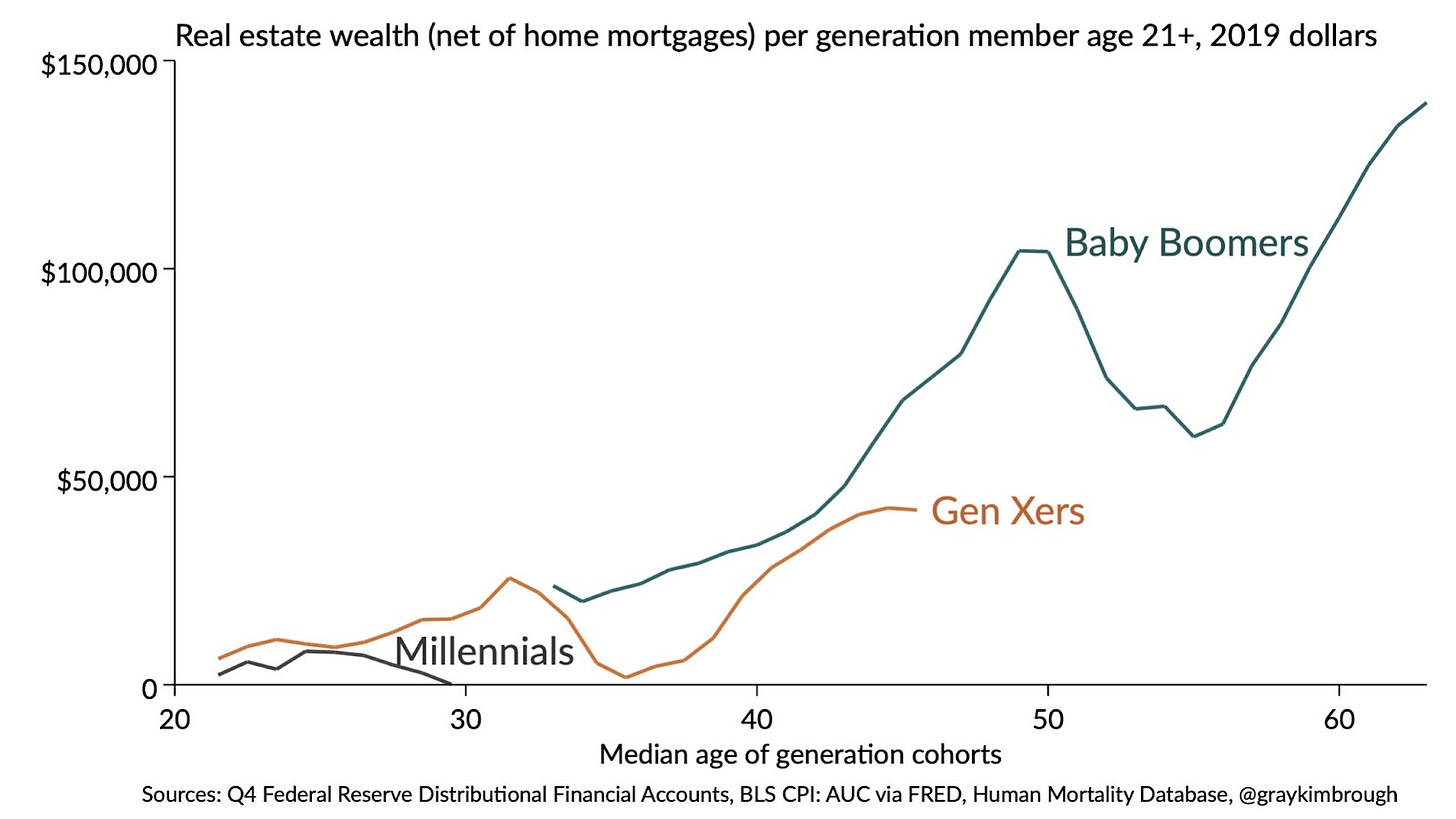

So what’s causing all of this? Oh gosh. We have a problem of constrained supply, wealthy boomers (even though 5% of boomers own 60% of that generation’s financial assets), and millennials aging into homes - so it’s really a perfect storm.

Source: Gray Kimbrough

It gets worse: You also have a ton of shortages (Ali Wolf has amazing tweets on this) - doorknobs, the little plastic things that you stick on chairs so they don’t scratch the floor when you scoot, etc. Home sale-to-list ratios are above 100% meaning people are putting their *whole* financial selves into trying to buy a home.

But - The Fed is shrinking the balance sheet and raising rates! That puts upward pressure on mortgage rates (rates have ticked up to almost 5% after being near 3.36% a year ago, according to MBA) - which means that people are no longer applying for mortgages (mortgage demand is down 40% y/y) - because ~expensive~. So we could see some easing in housing demand, which might create a bit of space for prices to breathe.

But x 2 - The natural question that follows with this sort of housing situation is “is this 2008 2.0” - and the answer is no, not really. People are financially healthy (mostly) and the credit of the borrowers is much different than 2008 - and also big banks aren’t securitizing everything (mostly).

We mainly need to build - but we’ve overregulated and basically squashed out a lot of progress that could be happening here. So will it burst? Maybe. But supply and demand is a powerful force.

How will the lessons of 2021/2022 affect how the Fed goes moving forward?

Joey:

It’s always hard to predict how current events will affect policy in the future, especially when those current events are part of a once-in-a-generation pandemic. The lesson of 2020 was “early, rapid, and strong actions to protect the financial sector can stop a crisis” and “proper monetary policy can support a rapid recovery in the real economy.” The lesson of 2021 was that despite the decades long trend of declining interest rates and the weak macroeconomy of the 2010s, it is still possible to overstimulate the economy.

My biggest worry is that future Fed officials will forget the lessons of 2020 by over-learning the lessons of 2021. The dominating trend of high income economies over the last few decades has been dramatic underinvestment and underconsumption—we have all been living more impoverished lives due to macroeconomic mismanagement. 2020 proved that a proper response to a crisis could prevent disaster, and we will need to respond properly to the climate crisis, housing crisis, and population decline. That’s going to require a Federal Reserve that’s still attuned to downside risks within the economy, and I worry that the Fed could once again become too fixated on inflation for its own good.

Kyla:

Their dual mandate is indeed dual: I think that the Fed has been really focused on jobs for a while - they really struggled with getting inflation off the ground over the past ten or so years, and now inflation is very clearly the main focus.

But for a long time, the labor market has not been great - it’s been okay, sure, but not great. So the Fed made it really clear when the pandemic happened that they would be really focused on a strong labor market

So inflation is pretty political: But then the narrative sort of shifted once inflation started spiking to “ah well, if we fix inflation, we can fix the jobs market” - price stability *precedes* maximum employment.

The Fed’s importance: I also think that the Fed has become a really big component on the market - people watch Fed meetings like some sort of financial superbowl. And the Fed owns a large portion of the bond market now, right? According to Nick Timiraos, “The Fed’s portfolio doubled to 36% of GDP last year from 18% in September 2019. It holds $5.76 trillion in Treasurys, or 24% of the market, up from 12% in September 2019. It holds $2.72T in mortgage bonds issued by government related entities or 31% of the market (vs 20% in 2019)” So not only are they influential psychologically with what they say, they are also influential in actual physical holdings - and the eventual rolloff and selling (one day) of those could be interesting.

So I think that they’ve learned that they are Important - they’ve always been important - but what they *say* matters, a lot.

What is your advice for students who want to do what you do?

Joey:

I get asked this question a lot, and to be honest I am always intimidated by it. Unlike Kyla, economic analysis is just a passion project for me—something I do often but doesn’t pay me a dime. My day job is completely unrelated to the things I write about in my blog, so it’s not like I “made it.” I still consider myself an aspiring economist, nowhere near a real economist. So discount what I say a bit, but here’s what I would say to someone in high school or college.

First, stay in school. All the documented evidence is that extra years of schooling have immense positive effects no matter what you do (my favorite fact on this is that 1930s mobsters who had more years of schooling earned more money through criminal enterprise). “Learn to code” is trite advice because it’s good advice, so here’s what I’ll add: learn to code by repeatedly iterating on something you’re passionate about. I’ve learned more of the programming language R in 9 months of writing Apricitas than I did in 4 years of college because I was passionate about doing better and better things for Apricitas in a way I never was for college classes. Finally, consciously build a social support network: search for people who will care for you, support you, and challenge you to be better. Spend as much time as physically possible with them.

Kyla:

I had a nonlinear path (kind of) to where I am now. I had a finance blog in school, wrote for Seeking Alpha, traded options—I was iterating on finance before I was ever in the “real world”. But I also sold cars, did research internships, etc—I basically wanted to keep all my options open for everything. I chose my first job at Capital Group because it was a rotational program—it wasn’t going to be one job, it was going to be a new job every 3 months. When I left Cap Group to join a tech startup, I was mostly just trying to find my footing after realizing that I had to follow my heart—which involves both education and creation. So my advice would be:

Remain open—talk to as many people that you can, do as many things as you can, and don’t let fear dictate what you do/don’t do

Don’t give up on yourself—I came from a nontarget school, had no network, knew nothing—you have to be your own biggest fan

Never underestimate the power of questions—Ask a lot of things from both yourself and the world. Remain curious—finding things interesting is very different from applied curiosity. Explore as much as you can.

What your hottest take that doesn’t have to do with finance or econ?

Joey:

Hockey is the best spectator sport out there, and it’s not even close. The game has much better flow than the interruption-heavy sports like baseball, basketball, or (American) football but keeps higher tension than soccer due to the increased frequency of shots on goal. Power plays are far and away the best penalty system out there, striking a careful balance between punishing teams for breaking the rules while preventing referee decisions from determining the outcomes of games outright. Allowing fights helps regulate players’ in-game conduct while creating intense personal and team rivalries. Playoff upsets are reasonably possible (unlike in the NBA) but bad teams aren’t eliminated for one bad game (unlike in the NFL). The pandemic was a major interruption in my consumption of sports content, but I am glad to finally be watching hockey again.

Kyla:

I’m going to do this in two parts.

I think that humans are really beautiful and lovely and amazing - there’s so many cool things that we do, like build and love and create. Sometimes humans really suck (usually clouded by money or power or whatever) but most humans are really good people.

On the flip side of that, I think that we are all really sad and it’s only going to get worse. I don’t know what to make of it—but I truly think social media has erupted a part of us that is meant to have empathy and love, and skewed it to anger.

I think that we have a passion crisis where people feel completely disconnected from the world, and that’s largely because we don’t spend enough time *in* the world. I think that everyone does have a passion, but we historically haven’t been encouraged (or supported) to explore it.

I really enjoyed this collaboration. Great advice!